Housing, Homelessness, Commercial Development and Neoliberalism

November 24, 2018Noongar Settlement: an update

December 4, 2018Jerusalem has been a flashpoint for global tensions for decades. This comes from it being a critically important site for three of the world’s oldest religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam. These Abrahamic religious traditions all consider it a holy city.

Some of the most important (and sacred) places for each of these religions are found in Jerusalem and the one site shared between all three is the Temple Mount. The interaction between these religions has also been influenced by historical events, that are sometimes externally driven.

A better analysis of history, belief and fundamentalism in particular will help contemporary commentators to understand that while each religion is separate and distinct, they are also deeply connected.

When creating the modern nation of Israel in 1948, the United Nations General Assembly intended for the city to be an international enclave because of its shared stature for Christians, Muslims and Jews.

Nonetheless, it almost immediately became a focus for violence and conflict after Israel was established, when Jews and Arabs fought in the streets. It subsequently became a divided city after a 1949 armistice between Israel and Jordan. Israeli forces took control of the city during the Arab-Israeli war of 1967.

Later, in 1980, the Israeli parliament – the Knesset – decreed Jerusalem the nation’s capital, even though Palestinians also hoped to one day make it the capital of a new Palestinian State.

The religious importance of this city dates back to the days of the Old Testament and 1050 B.C. when Israel’s King David conquered Jerusalem. His son, Solomon, expanded on the construction David began, building the Temple on the Mount that would later be finished by Herod (a remnant of the western retaining wall for the temple ruins is now the Wailing Wall or Western Wall of Jewish prayer and pilgrimage). In close proximity to it is the Muslim Dome of the Rock from where Mohammed ascended, and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites.

In addition, Christian pilgrims travel to Jerusalem to walk the path Jesus walked and visit the Christian Church of the Holy Sepulchre built by Crusaders in the 12th century over the supposed site of his tomb.

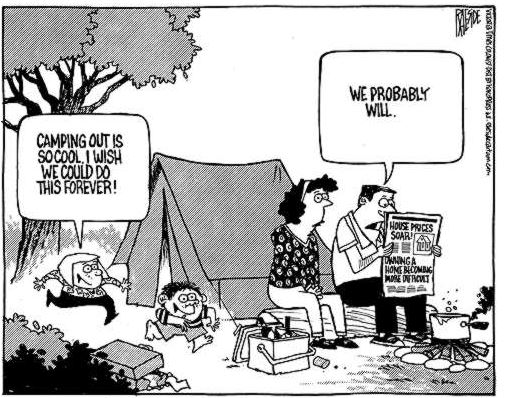

Due to the city’s shared religious significance, the United Nations declined to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and virtually all nations, including the United States, maintain their embassies in Tel Aviv.

Between 1910 and 1920, “The Fundamentals”, consisting of ninety essays were published by a branch of Christianity; and so the term ‘fundamentalism’ was born. More often than not it is a form of Christian extremism.

Since then, fundamentalism has also extended beyond Protestantism, to Catholicism (where it is called “traditional Catholicism” and seeks to reverse the reforms of Vatican II), as well as in other religions, notably Judaism and Islam.

Fundamentalists desire to return to some supposedly golden era, and to live as much as possible according to ancient rules and textual authority. They hold a nostalgic view of a utopian past, when their religion was pure and which they seek to return to. Islamic fundamentalists, for example, yearn to return to the purity of Islam, and to live similarly to how they consider the prophet Muhammad and his companions lived in seventh century Arabia.

Fundamentalists reject modern scriptural criticism, science, abortion and euthanasia as well as modernism and secular liberalism, pejorative terms used to describe their opponents.

They affirm that the Scriptures are perfect, although in practice fundamentalists do not apply equal authority to every word of Scripture.

Hence, any criticism, however small, is taken as a criticism of the whole religion, which helps explain the fundamentalist reluctance to compromise.

Whilst nearly all Christian fundamentalists believe that the Bible is the word of God, there is an almost even split between those who believe that everything in the Bible should be taken literally and those who do not. Proof-texting is a common fundamentalist practice. It uses scriptural passages to draw conclusions without regard to historical context, lifting a text from its location both in time and in narrative in order to solve an unrelated theological problem.

Jewish, Christian and Islamic fundamentalists share a similar understanding of prophecy and 22 prophets are shared by these three religions, most famously Abraham and Moses. Some fundamentalist followers believe their current leaders have received divine approval and speak God’s truth.

Whilst most fundamentalists agree prophecy has come to an end (though it will be restored at the end times), they naturally disagree when. For Jews, prophecy ended with Malachi. Christians believe prophecy returned with Jesus and Muhammad is the seal of prophets for Muslims – the revelation each brought is believed to supersede the previous revelation.

In recent years, fundamentalist leaders have made odd bedfellows: conservative Catholics and Protestant fundamentalists work together to support pro-life movements; evangelical Christians and Israeli fundamentalist Jews support right-wing Israeli government policies; and Islamist fundamentalists and anti-Zionist Jewish fundamentalists collaborate in opposition to the state of Israel, and so on.

Jewish fundamentalists generally focus on issues related to Israel and have emerged as a significant political force today, seeking to impose some biblical and rabbinic laws on the modern State of Israel in areas including education, food, transportation and sovereignty over holy sites. There is a widespread tendency to speak of the State of Israel in language, which echoes biblical prophecies.

Some Christian fundamentalists, commonly called Christian Zionists, are well represented among Southern Baptists in the United States and have considerable influence on US policy, demonstrated by President Trump’s decision to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Other Christian fundamentalists join their Jewish partners in calling for the construction of a (third) holy temple in Jerusalem, believing that this temple, alongside the creation of the Jewish state in 1948, are prerequisites for the second coming of Jesus. Some of these same fundamentalists also actively seek the conversion of Jews to Christianity.

Whilst sacred land is important to Jewish, as well as to Sikh and Hindu, fundamentalists, it is unimportant to Christian or Buddhist. Similarly, proselytism is central to Christian and Muslim fundamentalism, but not Jewish or Hindu.

This subject warrants much deeper investigation, but whatever the similarities and differences, fundamentalism is a major and increasing global force, gaining significant ground against liberal and secular counterparts.

All fundamentalists perceive themselves as believers under siege and attack, who are attempting to preserve their distinctive identities in the face of modernity and secularisation. There is a distinct group of insiders and all others are outsiders. Insiders are nurtured and cared for. Outsiders are cast off and fought.