Love a Muslim Day?

April 6, 2018

We whitewash the history of “whitewashing” Indigenous children.

June 25, 2018Bishop Curry’s Sermon on ‘Love and Fire’ the weekend has thrown up lots of commentary, both for and against. Surely, it has also raised fundamental questions regarding belief.

What does belief mean to a post-modern society? In the matter of faith and unfaith, the story is everything – not the definition, but the real life experiences about ending and beginning again, the search inwards, the meaninglessness, the discovery. It is the Christian story that awakens our connection with the history of faith. As liberation theologian Jean-Marc Ela reminds us, that story translates into “the context in which people live, taking account of their creative efforts to construct a future that will be different from their past, a past so cruelly marked by … domination”. In the process, we challenge the forces of violence, injustice, racism and sexism that cripple so many people. Faith opens to the touch of beauty.

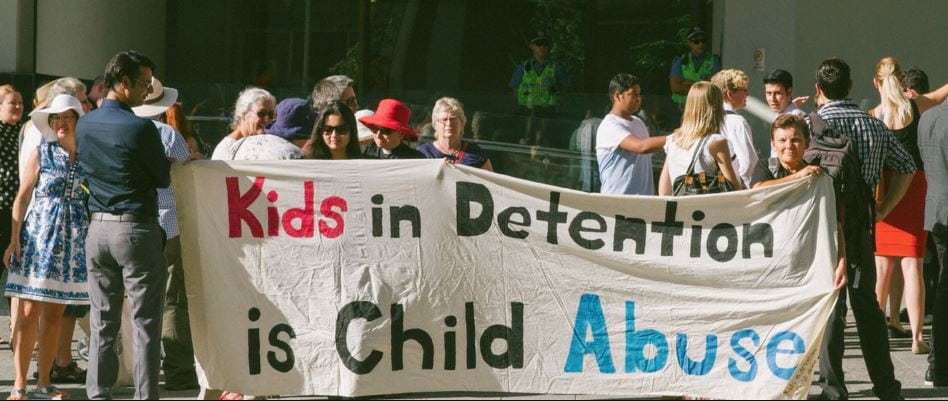

Curry boldly raised the matter of slavery, which in turn raises questions of empire and colonisation.

And how do faith and unfaith respond? Unfaith denounces, condemns and, worst of all, is separate from the human tragedy. Faith holds the human condition as precious to God and believes always that the human face of God is turned to each of us in mercy. As faith and unfaith are elusive, so too are the categories victim and perpetrator. There is a deep longing for connection; it is not surprising that the essence of faith is reconciliation. One of Carl Jung’s succinct observations has become a mainstay of my theological thinking: “One does not become enlightened by imaging figures of light but by making the darkness conscious.” To image figures of light is the ultimate projection of unfaith; it stands against the world; it pretends to know; it dogmatises. To make the darkness conscious is to find our true role as prophet.

Aboriginal people regularly experience disadvantage and conflict of cultures. For many the bases of their self-confidence are eroded; for some life scarcely seems worth living at times. To make the darkness visible we must take to heart those who are marginalised by mainstream Australia. The needs of the powerless and those suffering injustice lie at the heart of the Christian faith. The sheer scale of the problem of Aboriginal mental health and suicide is a critical backdrop for any reflection on faith and unfaith.

God speaks in and to every place and every silence “even to those places where no other word has yet found entrance”. The art of careful study of the Bible and its message of freedom and reconciliation are the mainstay of vital belief. The Bible exposes our hidden idolatry and enlivens us to the beauty and tragedy of the world about us. Only then will injustice and intolerance, discrimination, sexism, homophobia and violence be seen in their true light. We will have touched the centre of our being and found there the forgiveness and compassion of God.

For too long we have drawn narrow boundaries between church and world, faith and unfaith. Our debates are about internal structures and our ethics tilt at community values without properly assessing their philosophical merit. There is a world of search and discovery beyond our borders: some of it needs to be affirmed as the leading of God’s Spirit; against some we need to speak with the passion of prophets.

Faith and unfaith are defined by the conflicting values, the gods and demons that struggle for the Australian soul. This comment of evangelist Mark Van Houten sums up my own thinking about belief and unbelief: “To transform culture, God actively creates and re-establishes humanity – self worth, respect, dignity, agapic love and community among his people”.

thanks to Bill Lawton