The Politics of Scott Morrison and Prosperity Theology

October 9, 2018

Housing, Homelessness, Commercial Development and Neoliberalism

November 24, 2018‘Across the road is a missionary journey’[i]

Please note: this is very much a work in progress and is an iteration of perhaps 35 years of my thinking – it is not all original, nor is it referenced

For the radical disciple, it is what D. Bonhoeffer described: ‘It is not some religious act, which makes a Christian what he or she is, but participation in the sufferings of God in the secular life.

This is partly the story of my thinking – Part 3 of an Australian theological pilgrimage (or is it part 4?); earlier elements of it are published on my blog. Key themes are as follows:

- Urban mission

- Radical discipleship

- Inclusion, and

- Outside mainstream, ‘the Other’.

The Challenges of Urban Mission

- In 1700 fewer than 2% of the world’s population lived in urban places. Beijing and London were the only cities that had populations surpassing one million.

- By 1900 an estimated 9% of the world’s population was urban. London was then the world’s only “super-city”.

- By 1950 27% of the world’s population lived in cities and 73% of the world’s people lived on the land.

- By 1996 however, the world was growing by 86 million people a year and for the first time more than 50% of the world’s population lived in cities.

The United Nations—which offers the most conservative growth estimate—projects that by 2025 over 60% of the world’s estimated 8.3 billion people will live in urban areas.

There are many challenges in urban areas:

- traffic,

- pollution,

- noise,

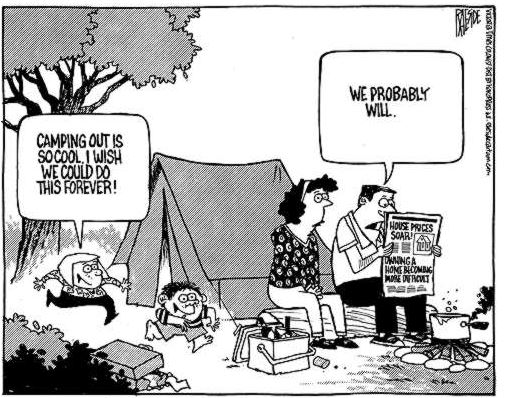

- high cost of living,

- crowded and often substandard living conditions,

- economic disparity, stress,

- psychological overload resulting in mental illness,

- long hours of commuting, and

- violence/crime.

Nonetheless, people continue to be drawn to the city through migration and immigration; this partly because cities provide people the best hope of education and income.

It is harder to develop stable churches in urban areas, but those areas also creates great opportunity for mission.

Urban (meaning and definitions):

- City: A centre of population, commerce, and culture; a town of significant size and importance.

- Inner city: The older and more populated and (usually poorer) central area of a city.

- Urban: of relation to, or located in a city; characteristic of the city, or city life.

- Ghetto: a section of a city occupied by a minority groups (or groups) who live their because of social, economic, or legal pressure.

- Community: a district or area with distinctive characteristics.

- Downtown: the lower part or the business centre of a city.

- Suburb: usually an area or community outlying a city.

- Metropolis: a major city, especially the chief city, of a country, or region

- Cosmopolis: A large city inhabited by people from many different cultures.

Key questions:

- What is God’s mission to the city?

- What is ‘urban mission’?

- Is urban mission is bringing good news to the city?

The need for contextual churches.

While, there is a great barrier to urban mission; it is not in the cities themselves nor in urban residents, but in the church. The awareness of most churches and leaders is limited and are often not interested in urban mission; some may even be anti-urban mission.

We have witnessed a withdrawal of active Christian engagement from urban areas; some people term this “suburban flight” as people head to the burbs with greater affluence and relative cultural hegemony.

Many ministry methods have been forged outside of urban areas and then simply imported without much thought; this creates unnecessary barriers between urban dwellers and the gospel.

When ill equipped clerics go into urban areas to establish ministry, they find it hard to communicate and connect urban people. They also find it difficult to prepare Christians for life in a pluralistic, secular, culturally engaged setting.

Just as the Bible needs to be translated into readers’ vernacular, so the Christian message needs to be embodied and communicated in ways that are understandable to people who have grown up outside of the church. This raises the question of what are some key characteristics of a church that is seeking to be missional, contextualized and immersed in urban ministry?

Firstly, people in urban ministry are aware of the sharp cultural differences between different racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes, while people living in more homogeneous places are often blind to how many of their attitudes and customs are very particular to their race and class. In short, effective urban church leaders must be far more educated and aware of the views and sensitivities of different ethnic groups, classes, races, and religions. Urbanites know how often members of two different racial groups can use the identical word to mean very different things. Consequently, they are very careful when approaching issues that racial groups see very differently.

Second, traditional Christian ministries tend to give believers relatively little help in understanding how they can maintain their Christian practice outside the walls of the church while still participating in the world of the arts and theatre, business and finance, scholarship and learning, and government and public policy.

Third, most Anglican churches are middle-class in their corporate culture. People value privacy, safety, homogeneity, sentimentality, space, order, and control. In contrast, the world outside the church doors is filled with ironic, edgy, diversity-loving people who have a much higher tolerance for ambiguity and disorder. If a church’s ministers cannot function in an urban culture, but instead create a kind of non-urban “missionary compound” within it, they will discover they cannot reach out, convert, or incorporate many people in their neighbourhoods.

Fourth, the non-urban church is ordinarily situated in a fairly functional neighbourhood, where social systems are strong or at least intact. Urban neighbourhoods are vastly more complex than other kinds, however, so effective urban ministers learn how to exegete these neighbourhoods. Also, urban churches do not exegete their neighbourhoods simply to target people groups for evangelism, though that is one of their goals. They look for ways to strengthen the health of their neighbourhoods, making them safer and more humane places for people to live. This is seeking the welfare of the city, in the spirit of Jeremiah 29.

In Australia urban mission and radical discipleship have had a confluence of thinking over the last 30/40 years – a lot of the thinking also emerged form youth work praxis and para church movements.

People often grieve over the state of our cities, as though the deprivation, growing squalor and crime have never been so bad before. This is not necessarily true and historians help us bring more balance and a healthier perspective. The Christian should be able to bring hope in that urban work today can be set alongside examples from the past: William Temple, (other examples)

Clearly, earlier methods would not be appropriate now – with the dominance of neoliberalism (with shift from citizen and community to consumer and economy), great technological change (particularly in communication and media), and the changing place of religion and faith in our culture/society – yet it is always encouraging to see past themes recurring in modern contexts:

- going to people where they are,

- indigenous leadership,

- the suitability of clericalism and ministerial training, and

- the hidden strength of lay ministry.

In today’s context of a rapidly changing economy, means of communication, media/social media – not to mention broader society and culture – these themes raise difficult questions and wicked problems for Christians at large and not only those seeking to make a difference in the city. For example, the problem of well-heeled middle class suburban faith.

Looking Abroad

UK: The emergence of urban mission in the UK is strongly established with perhaps 40 years of historical development and is growing a unique theology. Books, groups, conferences, leadership and projects are key indicators of a movement and that urban mission is grounded in deep theological reflection and analysis.

David Sheppard’s ‘Built as a City (1975) was a seminal British book to take the urban mission agenda seriously. But it was also the analytical work of other pioneers like Ted Wickham’s volume on Sheffield, ‘Church and People in an Industrial City’ (1957) that outlined the realities and called for a Christian response.

Other people and groups were enormously influential and developed the key themes in the 60’s and 70’s, for example:

- Jim Punton and Michael Eastman from the Frontier Youth Trust (working with marginalized young people),

- the Evangelical Urban Training Programme,

- the Shaftesbury Project (urban research), and

- Christians for Racial Justice

During the 1980’s networks emerged like the:

- Evangelical Coalition for Urban Mission (ECUM),

- radical Christian Organisations for Social, Political and Economic Change (COSPEC), and

- Anglo-Catholic ‘Jubilee’ led by Kenneth Leech and Rowan Williams.

There were also denominational based initiatives like:

- Methodism’s ‘Mission Alongside the Poor’, and

- Anglicanism’s ‘Faith in the City’ which arose from the Archbishop of Canterbury’s ‘Commission on Urban Priority Areas’.

US: Jim Wallis, Donald Kraybill, Jack Sparks (Alexander?) – enmeshed with broader political agenda, peace movement, racism. Books and magazines have flourished, with Wallis’s ‘Sojourners’ magazine

underdeveloped

The Emergence of Urban Mission in an Australian Context

The ‘White Australia Policy’ assumed an ethnic and racial homogeneity for the English-speaking population that was indeed a false construction, negating the Indigenous. The ‘white’ community can be described using B. Anderson’s conceptual term from his political-science background. He states: “The modern nation, no matter how small or socially homogeneous, can only be an imagined community.” It appears that “Immigrants are often in the society, but not yet of it.” This also highlighted the historical disconnectedness and tensions in contemporary Anglicanism. Ministry towards First Peoples, migrants and refugees to this point had been largely lay ministry, achieved through dedicated lay parish women and men.

Anglican parishes, along with many in the wider Australian community, still clinging to its British roots, continued to proceed with the ‘imagined community’ through its (often nominal) adherents. They assumed cultural homogeneity in practice and theology, without recognizing the shifting sands.

In addition to the large-scale immigration programmes post WWII that has brought central/southern Europeans to Australia, there are also new population movements as a consequence of Australia’s geographic proximity to South-East Asia.

The problematic identity of the Australian Anglican church in society is discussed in Caroline Miley, The Suicidal Church: can the Anglican Church be saved? (Annandale, NSW: Pluto Press, 2002), see also her chapter: One People of God? Clergy, Clericalism and the Laity: The Laity, “One People of God? Clergy, Clericalism and the Laity”

This ‘stiff-upper lip’, ‘steady as she goes’, approach to ministry direction of Anglicanism represented ‘cultural hegemony’, a term Antonio Gramsci had coined in the 1920’s and 30’s. It is a sociological/political construct. {Antonio Gramsci, Quintin Hoare, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (New York: International Publishers, 1971).

‘Cultural hegemony’ by the ruling classes establishes a dominant culture to whom most others want to aspire and is used as a means of social control. Gramsci recognised the conforming and self-authenticating nature of a hegemonic culture amongst the aspirant classes, notoriously the collusion of influence between the Italian Fascists and Roman Catholic Church, prior to WWII.

The reliance on British immigration to feed into local Church of England churches fast became a myth. The whole world has broken into the Australian scene. This is another of the imponderable forces at work in the Australian consciousness and society; the isolation of this land is gone forever.

What we need is not so much Richard Hooker’s (1554-1600) dictum describing historic Anglicanism as committed to ‘scripture, reason and tradition’, but rather to ‘scripture, reason and mission’. We need a remarkable, contemporary balance. We need an understanding of unlocking one of the great strengths of Anglicanism – its laity.

Bill Lawton: a former lecturer at Moore Theological College returned to parish ministry. Representing a socially radical vision Bill was extravagantly compassionate and profoundly reflective, and the study of his experience and thought are used to bring a stronger theological perspective on the ministries at the heart of this paper. Lawton was Rector of inner-city St. John’s, Darlinghurst from 1989-to 1999). Theologian and historian Lawton had been on the staff of Moore College for 32 years as Head of Church History and Dean of Students. In 1986 he gave the spell-binding 1986 Moore College lectures on the challenges to Christianity in secular Australia. At St John’s, Darlinghurst, he followed the Rev John A. McKnight (1986-89), under whose ministry former Israeli nuclear technician, Mordechai Vanunu, had converted to Christianity and subsequently revealed to the world Israel’s nuclear capability.

Lawton was from the minority ‘radical evangelical tradition’. He formerly had been a protégé of D.B. Knox, Principal at Moore Theological College, 1959¬1985, and had been lecturing in the College since his early twenties. He earned doctorate, examining Sydney evangelicalism in his thesis turned book: “The better time to be: the Kingdom of God and social reform: Anglicanism and the Diocese of Sydney, 1885 to 1914”. His experimental ministry in Darlinghurst was in the very heart of Sydney, the history of which he had previously brought to life in his thesis.

St John’s became the testing ground for his well-researched experiment. Previously fascinated by ‘the God is Dead’ movement which hoped to address secularism, Bill was now transfixed by the development of Liberation Theology, which addressed social disadvantage. He had already in teaching religious history chosen to use such paradigms as the liberation movements which spoke to his concern for the gospel and social justice. Despite teaching history at Sydney’s prestigious Theological College, he believed much was to be learned from contemporary Sydney.

The study of missions in the urban context was not then readily understood or applied to the everyday life of Sydney parishes, which, too often, either by design or ignorance generally followed an English speaking, homogeneous unit model created by and for middle-classes. His paradigm-shift acknowledged a new level of challenge to middle-class Christianity posed by post-modernism, secularization, and immigration policies resulting in culturally-pluralistic communities. He favoured the study of ‘urban missiology’ and the deliberate creation of more open and inclusive congregations.

Paradoxically, this needy area was now relatively gentrified, with the well-to-do living ‘cheek by jowl’ with the urban poor, sex-workers, the homeless, and those devoted to lives of organised crime.

St. John’s Darlinghurst began to address ministry to those recognised in Bill’s words as “street-people”. The ministry of “Rough Edges” began life as a coffee-shop, drop-in centre. It included sex-workers, “street people”, including the mentally ill. From “Rough Edges” began a Thursday night service with street people. Here they wrote their own prayers and sang their especially written songs for their worship service. Fifty or so volunteers began training from the congregation whom Bill described as “genius staff”. Undergirded by their fragility and giftedness, they were willing to serve, and began pouring themselves out into the local community like healing salve.

Lawton gives a literary snapshot of the parish, in his own inimitable style:

Margaret and I work in the parish of East Sydney – better known to you by its tawdry and accidental centre, Kings Cross. The Cross is about 200 metres of tired sex parlours, punctuated by quick food outlets, money changers and banks. The smell hits you first – stale food, stale sex and the gagging pungency of underground drains and surface vomit. The grey-green faces of girls, struggling with their last heroin fix, their eyes hooded and their bodies in slow motion slump, tell you that this is a place of despair and death. And some are so young and once so pretty … Here is reckoned to be the third wealthiest part of Sydney. At the south, the parish is bordered by Oxford Street, with its annual [Gay and Lesbian] Mardi Gras, its myriad cafes and bars and St. Vincent’s Hospital. St. John’s stands on top of the hill, stately, powerful Revival Gothic. Its splendid spire, still visible from one harbour vantage, was once a marker for sailing ships. … This is where God’s people live as evangelists to the streets, who are, according to social theologian William Pannell, ‘converted by the city itself, by the squalor and misery of the poor’.

Lawton describes thus his philosophy of ministry in an inner city parish:

Mark Van Houten of Chicago’s Northside has challenging insights into urban ministry. He writes: ‘Christians are able to evangelize most biblically and effectively as they incarnate Christ … that is when their presentation of God is not anchored in the ontological, but in the functional attributes of God’ … what we keep discovering in East Sydney is that God has to be interpreted, incarnated, in the human context.

During the nineties this parish became one of the epicentres addressing the AIDS epidemic in Sydney. Hospices in the parish were attached to major hospitals, such as nearby St. Vincent’s. The stigma attached to those afflicted was rife as whole communities and estranged families struggled to come to terms with what many mainstream Christians believed was the “gay plague”. According to Bill:

One thing has not changed: the inner city is still a dumping ground for these modern day untouchables and the human run-off from Sydney’s safe middle-class suburbs is growing every year. In many cases the funeral service is the church’s only contact with the consequences of AIDS.

In describing ministry experience facing this most difficult of issues, his ministry experience reveals:

This is the reverse of all our expectations. We learn to see the beauty of Christ in the face of the poor and the outcast. This is nowhere more surprisingly met than among those who live and die with HIV/AIDS … You wonder, have they ever faced the tragedy of their own alienation to touch and be touched, longed to live in a community of restored relationships. … We are travelling with people into the centre of divine love, seeking the embrace of God’s forgiveness and restoration.

The short-comings of the homogeneous unit principle[ii] were well demonstrated through St. John’s Darlinghurst. It represented an excellent example of ministry to the inner city margins as well as attracting Sydney’s contemporary literati and social thinkers. This contemporary church growth example, (the congregation grew from an Easter service of 5 people to about 300) was indeed the complete reversal of the power and might of the ‘homogeneous unit principle’ because of its inclusive agenda.

In June, 1994, at the suggestion of David Claydon, Federal Secretary, CMS (1988-2002), Bill Lawton and the Rev John McIntyre, Rector St. Saviour’s, Redfern (1990- 2006) attended a Chicago, U.S. conference titled: ‘Prophetic Voices of the people of God in the City, The Birth of a Vision’ conducted by the Seminary Consortium for Urban Pastoral Education. Bill comments:

“The conference brought us face to face with the realities of American society. Each speaker addressed the horrendous impact of racism. The preachers almost all of them Afro-American spoke of the appalling destruction of their society, through guns and violence in the streets. They pleaded for tolerance and the breaking-down of old prejudices … We were dismayed to see the abandonment of the inner urban areas by the mainline churches. Yet we saw a continuing presence through these community churches and wondered with what we were being confronted with might not yet be a picture of Sydney in twenty years’ time.”

Lawton’s Darlinghurst ministry illustrated the adage “mission is the mother of theology”, a key principle in Sydney’s radical minority evangelical tradition, characterised by a strong focus on evangelistic/social justice engagement. Roman Catholic van der Watt identified ‘justice and peace Evangelicals’ ministering the gospel as they saw it, whilst seeking greater engagement with their local community, as they recognised it.

This was not merely the historic charity “hand-out” model, but rather an attempt to address the inherent causes of the disadvantage, through bringing in the wounded to an oasis of Christian community. This ministry, according to Lawton, sought to re-introduce the historic tradition of the English evangelist, John Wesley (1703-1791), by using his concept of “social holiness” translated into the post-modern world as “social wholeness”. For Lawton, this was grappling with the very nature of inequality as well as calling for a life-changing response to the gospel in his congregation. Social Psychologists speak of the closed social behaviour of minorities which naturally exclude ‘the Other’ in terms of status, class, and hierarchy. But Lawton sought a congregation which was a different sort of minority. His ministry would attempt by way of its intentional community engagement to consciously seek and implement inclusion as well as where possible address disadvantage. This involved experimenting with the liturgy in order to become more inclusive, despite being criticized for having ‘sold out the gospel’. From his own lived experience, grappling with the issues of contextualizing the gospel for his parish and beyond, he describes the decade-long journey with his characteristic disarming honesty:

“Once upon a time I read the Bible through the medium of middle class culture and on the basis of power. I now find myself in a place where there seems to be no power, and where the people appear to have nothing. But Christ is present in the lives of these people!

I’ve learnt something in the last six years that has transformed my life. I’ve learnt that I live with people who’ll forgive anything I do except lie to them … If the church is to survive as more than a rump of the past, then the Church … must break down our barriers and cross over to people outside the Church in a spirit of openness and acceptance.”

St. John’s, Darlinghurst ably led was crossing the barriers of social class, race, religion, colour and mental illness in and through its community outreach ministries. It bridged the ‘socio-political’ divide because its ministry sought to address physical as well as spiritual need. The church’s congregation attempted an honest and even experimental engagement amid its community. In it ‘theology informed praxis’ and the reciprocal effect, ‘praxis informed theology’ through the experiment of contextualization. The often brutal meeting point between church and the wider community is where the evidence of theory is tested. This process in effect gave the church and its congregation its mission, its compassion and the affirmation of its identity, tested through the crucible of belief and its practical outworking. Its life was found not merely through its liturgical symbols but through its praxis as lived within the context. It offered a more focussed Christological and scriptural response to the most acute human need. Here the local church, Christ’s flag bearer, whilst being immersed in Sydney’s ugly ‘dark side’, was unafraid. Much was at stake in the decade-long ministry of Lawton and the ‘genius ministry team’.

Radical Christian social critic, Jim Wallis, who toured Australia with Lawton in 1995, told the story of a black street preacher, whose church was sprayed with bullets on the inside during a gang-war. The moral? ‘If you don’t take the Church to the streets, the streets will come to the Church.’

Athol Gill

As a community builder, Athol Gill was founder and leader of two intentional communities- the House of Freedom in Brisbane and then the House of the Gentle Bunyip in Melbourne. Gill has been described as ‘an innovative leader of the Christian community movement in Australia’.

The communities of the House of Freedom and the House of the Gentle Bunyip reflected Gill’s understanding that the pursuit of justice and peace were integral to the mission of the Church.

Gill welcomed the fact that the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelisation in Lausanne, Switzerland recognised that evangelism and social action were not mutually exclusive and w ere both part of Christian responsibility. Gill, however, was part o f a radical grouping at the Conference who went further and declared that to drive a wedge between them was ‘demonic’.

Gill emphasised the relationship between worship and mission. At its peak in 1982, the Bunyip community had seventy members living within walking distance of the community centre.

He was encouraged by the w ay in which, following the Lausanne Congress lead, evangelicals in many countries increasingly saw that commitments to justice and peace were ‘foremost to the gospel. On the other hand, he lamented that ‘the impact of these developments is not always present among some evangelicals’.

He produced a paper titled ‘Human Rights: A D own Under Perspective’. In this fascinating article Gill makes explicit a number of his interests and argues with reference to the bible and the poor that human rights and social justice are a concern for the whole church because they are a concern for God, not least as revealed in Jesus of Nazareth.

In pursuing his understanding of the gospel there were a number of issues which brought Gill into conflict with members of the wider Christian community.

Olivia Maclean

I know Olivia and am really inspired by this model – it is a bit different – but shows other Anglicans thinking outside the box!

Key Themes Developing and an International Movement

Behind all the national emphases the concerns of the wider Christian community were also developing. The Lausanne Conference (1974) firmly merged the relationship between personal faith and social action. The Australians took a lead in the ‘radical discipleship’ agenda there and this was further developed in Thailand (1980) where the radical leadership group committed to biblically-based social justice and subsequently produced resources and books on ‘Christian Outreach to the Urban Poor/Large Cities (1983). This was followed up with an emphasis on social transformation, in volumes like:

- Chris Sugden and Vinay Samuel’s ‘The Church in Response to Human Need’,

- Graham Young’s ‘Letter’s for Auntie Flo: Journals of a reluctant disciple’,

- Sugden’s volume on Radical Discipleship, and

- Waldron Scott’s ‘Bring Forth Justice’ which sought to integrate: mission, discipleship and social justice.

In the UK, the gathering momentum around ‘urban mission’ earthed these themes in a British context; with:

- Lewis Misselbrook’s “Residents of Council Housing Estates’,

- Eastman’s ‘Inside Out’ & ‘Young People at Risk’, and

- Colin Marchant’s ‘The Urban Poor’.

A new language was developing – justice, poor, cross-cultural, church-planting – a Christian vocabulary a new theology!

A number of books picked up these themes:

- Roy Josin’s ‘Urban Harvest’ (1982) ,

- David Sheppard’s ‘Bias to the Poor’ (1983)

- Michael Paget-Wilkes’s ‘Poverty, Revolution and the Church (1982), and

- John Vincent’s ‘Into the City’ (1982).

But it was the Anglican ‘Faith in the City’ report (1985) that raised the debate to the national and political stage. The report revealed both the structural dimensions and the Church’s weakness; in addition, it highlighted the political disease which led to Christian involvement in social issues. From that report came the ‘Church Urban Fund’ major questions about clerical training, new forms of Christian presence and an ongoing political debate about the nature of society.

Theological reflections were emerging from the inner cities themselves. The following volumes outlined the bleak social indicators and some positive Christian ministry in the inner cities:

- Dave Cave’s ‘Jesus is your best mate’ (1985) which talked about working in white working class culture,

- Pip Wilson’s ‘Gutter feelings’ about youth work in East London, and

- Marchant’s ‘Signs in the City (1985).

Further volumes tackled the social problem of employment and the accelerating growth of the other faiths that were growing in Britain’s urban areas:

- Michael Moynagh’s ‘Making Unemployment Work’ (1985)

- Christopher Lamb’s ‘Belief in a Mixed Society’ (1985)

- ‘Ten Inner City Churches’ (1988), edited by Michael Eastman, told the stories of congregations, and

- Philip Mohabir’s ‘Building Bridges’ (1988) was a significant contribution from the growing black-led churches.

Phases in urban mission and theological development

Alongside this theological development there have been a number of key phases. People who have been following this have been taken through major themes into a developing understanding of theological roots and responses.

Inner City was the first phase: this was the centring of attention on places. These were the areas where the social needs were greatest and the Christian Churches weakest. From these areas Christians fled and in these areas Christian presence was minimal and declining. But it was to these areas that immigrants came.

Urban Mission was a key term in the UK. This moved from the despair of failure into a mood of vigour and hope. Urban mission centred on outreach and social action – it was also compelled to move into political struggle. The emphasis on mission followed the recognition that church affiliation in the inner cities was below the level of all the major mission-fields of the world and has been so for generations – therefore church-planting was stressed and hundreds of new congregations were born. The emphasis on social action was carried in community programmes which drew Christians into areas of work such as: housing, employment, racism and poverty. This consequentially raised deep and profound theological questions. The constant balancing of Matthew 28 (Go into the world) and Luke 4 (Good News to the Poor) has been a feature of this phase and has had its influence on the wider church.

Urban Poor was a key-phrase from 1980. The World Council of Churches in Melbourne, the evangelical consultation in Thailand and the papal visit to Latin America all followed each other in quick succession and all saw the break-down of First World theological and institutional dominance, the recognition that the largest human grouping in the world was the urban poor, and the realisation that biblical teaching on ‘poor’ had been avoided by Christian churches and theological development around the world.

Liberation theology in Brazil was one manifestation of response. From all sides – demographics politics, social analysis – came the evidence for the shift in life-style from rural to urban and from sufficiency to poverty. Theology now became more political with the new stress on people arid the individuals ‘sinned against as well as sinning’ and political in the search for justice and equity.

Urban Priority began with the UK’s Conservative Government and was taken up by the Anglican Church. Urban Priority Areas were a’ serious political initiative to focus attention ‘on the inner city areas, the social programmes and urban people. When the church entered that arena the national theological debate took off. Discussion about the decisions on priorities involves taxes, discrimination and policies. –There followed a deepening and crucial theological-political debate about wealth-creation and poverty, about justice and stewardship, about power and prophecy. This debate continues to concern us all.

Urban Prophecy is the attempt to live out belief. The endeavour to earth, embody and proclaim – the Gospel in life-style and presence’ is expressed in many ways. The community movement is matched by deepening fellowship life in congregations; the Roman Catholic dispersal of the Orders into urban cells runs alongside charismatic ‘togetherness’; the gathering together of cultural congregations is paralleled by the arrival of hundreds of ‘incomers’ from suburban churches; and celebration worship links hands with political demonstration. These phases do not’ always occur chronologically but the last twenty-five years have seen these emphases gripping and shaping congregational life, denominational strategy and individual discipleship.

Radical Discipleship

Evangelicals are well known for their commitment to the Lordship of Christ, their embrace of the authority of Scripture, living a life of piety, and their involvement in witness and service (Bloesch 1988). It is hardly an overstatement that contemporary Evangelicals are quite activist in apporach.

While Radical Evangelicals share the above characteristics, their understanding of witness and service takes on some further challenges. In the following of Christ, they seek to be an incarnational missional presence in serving the poor. Some groups seeks to live five missiological principles: incarnation, community, wholism, servanthood and simplicity.

To live a life of radical identification in the urban areas of major cities is a major challenge. That some workers end up discouraged, burnt out or broken, should hardly surprise us. As a consequence, some years ago, people have added five values to their missiological principles: grace, beauty, celebration, creativity and rest.

The addition of these values is a recognition of the need for a more sustainable lifestyle and form of service. This is probing for a missional spirituality that animates one’s relationship with Christ, enriches one’s life in community and empowers a person for the long obedience in the work of evangelization, justice, peace-making and social transformation.

The focus of this section of this paper, then, is to show what sources Radical Evangelicals may draw on in order to deepen and enhance this move towards a more sustainable way of following and serving Christ.

In a nutshell, three sources of inspiration and animation will be briefly discussed:

- scripture,

- some themes in the long tradition of the church in history, and

- the value of one’s communal lived experience as a serving community.

Before we explore these sources of inspiration we will need to explain who are the Radical Evangelicals and define what we mean by a missional spirituality.

Radical Evangelicals

Radical Evangelicals emerged in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s as a broad-based movement of Christians who sought to integrate evangelism and the work of justice, live incarnationally among the poor, form Christian communities and critique aspects of Western culture and the Church.

The term came into prominence at the 1974 Lausanne Congress of World Evangelization when some two hundred delegates calling themselves “The Radical Discipleship Group” drew up a Response to Lausanne which called for a greater focus of the work of justice and service to the poor.

This diverse and global Evangelical movement emerged due to a complex set of contributing factors. These included: exposure to the counter-cultural movements of the 1960’s; involvement in new forms of urban mission among people alienated from church and society; interaction between Third World Radical Evangelical theologians and practitioners and their First World counterparts; impact of Charismatic Renewal opening people to the creative work of the Spirit; and exposure to more radical theologies such as Anabaptist theology and that of the liberation theologians.

To get some sense of what this global movement is about, it is important to note some of the theological emphases of Radical Evangelicals. These centre around the following themes:

- salvation is both the gift of Christ’s grace and the call to serve God’s Kingdom purposes in the world;

- salvation thus issues into a discipleship that is expressed in an imitation Christi that calls Christians to live the way of Christ in the world;

- salvation is never only personal in that it also calls us into community and solidarity;

- this community is the missional people of God sent by Father, Son and Holy Spirit to be a sign, servant and sacrament of the Reign of God; and

- this community in Christ is a community of worship, formation and identificational service to the world.

Radical Evangelicals place themselves in the whole story of Scripture since it reveals a God who is both wholly Other and who is wholly involved in the world sustaining it and redeeming it. At the same time, they are particularly impacted by the social justice vision of the Pentateuch; the OT prophetic vision of shalom, justice and the new community; the theology and praxis of the Jesus Movement as portrayed in the gospels; the in-breaking of the Kingdom in the power of the Spirit as told in the book of Acts; the Pauline Vision of new life in Christ in the new community beyond culture, class, gender and economic differences and the nature of the fallen powers that need to be exposed, resisted and redeemed; and finally the vision of hope in new heavens and a new earth.

In the light of these biblical and theological emphases, Radical Evangelicals see themselves as a prophetic counter-community in the world while being wholly engaged in the suffering and brokenness of the human community. Thus they practice radical hospitality. They seek to be a healing presence. They are committed to peace-making and the work of justice.

The challenge of living this kind of discipleship and mission clearly calls for a sustaining biblical vision, community and spirituality.

Defining Missional Spirituality

It is important that we gain some clarity as to what we mean by a missional spirituality.

By mission we mean joining in and cooperating with God’s redemptive, healing and transformative activity in the world (Bosch 1991). Radical Evangelicals are not comfortable with narrow definitions of God’s work in the world. The work of salvation blesses not only individuals but also communities. Evangelization and the work for justice go hand in hand. Soul saving and earth keeping are part of one mission.

By Christian spirituality, we mean the motivation and shape of a life of following Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit. Here also narrow perspectives are not helpful. Christian spirituality is not simply about prayer or meditation. It is about the whole gestalt of one’s life. The inner and outer dimensions of life belong together. Prayer and politics are within the gamut of one’s spirituality.

In the light of this we may define missional spirituality as follows: it is a way of life in Christ through the Spirit, supported by the community of faith and the spiritual disciplines that animates our whole life and our witness and service.

As a way of life, missionary spirituality, therefore, is not simply about praying for certain outreach or service projects. It is also about a prayer-filled life. And since it is a way of life in Christ – a cruciform life – it is not limited to some years of special missionary activity. The whole of life is to be in the service of Christ and needs to be animated by the sustaining Spirit.

Since a missionary spirituality is through the Spirit, it is more than hard work and self effort. It is a way of life and service that is initiated by the Spirit and sustained by that same Spirit. Moreover, such mission and service is not a solo effort. It is life and witness and service in community. It is joining hands with God and with others in the service of the neighbour. As such, missionary spirituality is a communal spirituality sustaining and fructifying acts of solidarity in the service of the poor.

Missionary spirituality is a way of life and service that embraces a disciplined life and the practice of the spiritual disciplines such as prayer, meditation, fasting, contemplation and service. What is of note here is that prayer and fasting are not simply a means to service but a way to God. And service is also a way to grow in God and not simply the outworking one’s relationship with God. Put differently, both prayer and service are ways to deepen one’s relationship with God and ways to express love to the neighbour.

Segundo Galilea expresses this well in his notion of the double movement of contemplation: the movement of transcendence and immanence. In the movement of transcendence we are invited to the contemplation of God face to face in the practices of biblical reflection, prayer, the practice of silence and the gift of revelation. In the movement of immanence we are invited to contemplate the hidden face of Christ in the faith community, the neighbour, the stranger, the enemy and the poor in the gift of service.

To put that in other words, in the movement of transcendence we meet with the God who nudges us to serve the neighbour and in serving the neighbour we are drawn to be with God in prayer and renewal.

Thus prayer and service belong intimately together. The spiritual disciplines and the work of justice are connected. Both are forms of worship and both are expressions of service. In the words of B.P. Holt this is “integrating one’s life in the world with one’s relationship to God”.

In summary, missional spirituality is relevant for all God’s people who seek to be witnesses and servants of Christ. Those who seek to serve Christ in particularly difficult circumstances, such as the Radical Evangelicals, don’t partake of a different spirituality but may well need to deepen that spirituality and express it in relevant ways in the challenges of serving the poor and the work of justice. This means, for example, that Franciscan spirituality can inform, shape and animate a member of Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, as well as an urban community worker, an academic and a politician. But how that form of missional spirituality is outworked will vary in each of these different settings.

Biblical Themes

Christian spirituality and the more specific focus on a missional spirituality has its roots in the biblical story. In the long history of the Christian Church this story has been appropriated in different ways leading to the rich spiritual traditions of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, the Benedictines, the Franciscans, the Reformers, the Jesuits, the Methodists and so on.

Beginning with the Old Testament we see that the themes of presence, redemption, peoplehood, and service are important themes. These could be reduced to the absolute basics of salvation, community and mission. But whatever the themes, the story is clear enough: God reveals himself, redeems a people who live in the worship and obedience of Yahweh and who are called to be a light to the world and a blessing to the nations (Isai. 42:6).

Within this frame there is an emphasis on the vision of God on the part of individuals (Gen. 15:1-2, Ex. 33:29-35, Isai. 6), and a sense of God’s presence in the corporate life of Israel’s feasts and festivals (Deut. 11:1-3). But despite the emphasis on presence there is also the sense of God’s absence (Ps. 22:1-2, Ps. 44:23-24) and the notion of wrestling with God (Gen.18:16-33, Job 40:2-4).

At the same time, the pages of the Old Testament are full of examples of individuals who pray (Gen. 15:2, Isai. 3:10, Ps. 51:1-2). Thus we see the complimentarity of personal prayer and a liturgical spirituality. And in the outworking of both we see the theme of prayer (Neh. 1:4-11) the practice of fasting (Lev. 16:29-30, 2 Chron. 20:3, Isai. 58:6), the practice of meditation (Ps. 119:15) and the spirituality of Sabbath (Ex. 20:11, Deut. 5:15).

Within the frame of this kind of personal and corporate spirituality we see two important themes that make a missional spirituality more concrete. The first is a spirituality of liberation. This is the Exodus theme. Having been freed by Yahweh’s redemptive activity (Deut. 15:15), the people so blessed, are to extend to others the same kind of liberation goodness (Deut. 15:12-15). This is most clearly expressed in the Old Testament social justice legislation (Sider 1978, 78-86) and particularly in the vision of the Year of Jubilee.

The second theme is that of a prophetic spirituality where in the midst of the kingship of Israel and the growth and increasing dysfunctionality of Israel’s power and the neglect of covenant and the growth of social inequality, we hear the call to restoration and renewal. This call for renewal became all the more pressing in the hegemony of priest, false prophet and king with the totalizing of religious and political power rather than the way of life of the people and its institutions based on Yahweh’s call to covenant and obedience. This spirituality calls for attentiveness to Yahweh, discernment of the signs of the times, a willingness to be misunderstood and to suffer, courage to proclaim what was not popular, a passion to challenge corruption and a vision to see the new age of Yahweh’s blessing.

Clearly these two specific themes within its broader framework constitute a source of inspiration and direction for Radical Evangelicals, who in the midst of a world of injustice, seek to proclaim liberation and be a prophetic people.

When we turn to the pages of the New Testament the themes are not so very different, except for the Christo-centric emphasis. In summary we could say that the vision is one of new people in Christ, the formation of a new community in Christ, living the way of Christ in the world and thus being agents of change and transformation.

More particularly focusing on the theme of spirituality we note the centrality on a Christological spirituality focused on a Christo-mysticism of what it means to be in and to live in Christ (Rom. 6:3-5). This is immediately augmented by a communal spirituality. Conversion to Christ involves the embrace of the body of Christ, the community of faith. Baptised into Christ by the Spirit, one is also called to water baptism and incorporation into the Church (I Cor. 12:13, Gal. 3:26-28). This means that both our spirituality and mission are shaped and sustained through worship, word, eucharist and fellowship.

Furthermore, the New Testament reveals an incarnational spirituality. This means first of all that the way of Jesus is formed in us (Gal. 4:19). Thus Jesus’ baptism, infilling of the Spirit, love of the Father, prayer life, proclamation, healing, community building and concern for the poor become our way of living and serving. And secondly, incarnational spirituality calls us to identification, being part of a group of people, joining with and serving a particular community, and particularly joining with the poor.

These themes are sustained by the practice of the spiritual disciplines of prayer, fasting, a voluntary asceticism (I Cor. 7:29-31) and nurtured by life in the Spirit (Jh. 16:14, Rom. 8:15-17).

The more specific emphases are clear: love of God and love of neighbour (Mt. 22:37-40) and service to the least as a way of honouring Christ (Mt. 25:34-36).

What we have pointed out so far regarding some biblical themes in both testaments is merely suggestive. It is far from exhaustive.

But the points I wish to make are clear enough:

- Radical Evangelicals need to root their vision for life for service and for a missional spirituality in the biblical story.

- The vision for mission and the contours for a missional spirituality do not begin with the events following the day of Pentecost. These are embedded throughout the entire biblical story.

- The theme of God’s redemption leading to salvation of a people who live in faith and obedience and service is foundational to the whole of the Bible.

- That witness, ministry and service need a particular orientation is clearly spelled out in the concept that we are to do God’s work in the world.

- That mission and service call for empowerment and sustenance is clearly what a missional spirituality invites us into.

Because the themes in scripture for living the life of faith, life in community and a life of service and witness are so rich, it should not surprise us that in the history of the Christian church something of this richness is displayed in the various Christian missional spiritualities that have emerged. To some of these we will now turn.

Drawing from the Tradition

Just as the discussion of themes in the biblical story was only suggestive, so the pointing to the rich history of Christian spirituality and its missional emphases, will be necessarily brief. The purpose is simple enough. It is to say to Radical Evangelicals don’t draw only from one tradition or from the more obvious historical examples. For example, Radical Evangelicals have much in common with Franciscan missional spirituality, but they can also learn much from Benedictine spirituality or Anabaptist themes.

This then brings us to the title of this article: Drinking from Many Fountains. And here are some of the traditions that Radical Evangelicals could draw from in deepening their life in Christ, their participation in Christian community and in empowering their life of witness and service, particularly in their work among the poor.

1 – The Desert Fathers and Mothers

There are many challenges for Radical Evangelicals in this movement with its beginnings around 250 A.D. which saw solitary hermits leaving ‘material comforts, worldly politics and secular social distractions’ to live in the Nile desert region living lives of ‘uninterrupted prayer and great physical mortification’ (Waddell 1998, xxvii). In time, this movement gave birth to what was later to become monastic communities (Waddell xxviii).

While this movement was largely a response to the post-persecution setting and the Constantianization of the Church which led Christians to find new ways of living in radical identification with Christ, it provides some key challenges for contemporary Radical Evangelicals and for a missional spirituality. These challenges may be summarized as follows:

- following Jesus may involve leaving one’s social setting and one’s job;

- to do this calls for a gospel critique of the dominant values of society and of the institutional church;

- the call to the desert is a call to renunciation and relinquishment. This involves a spirituality of asceticism;

- the challenge of prayer is not so much that we do nothing but that we recognize that personal and social change does not come about primarily through our activism but through the energizing and fructifying work of the Spirit;

- to live and serve on the margins of society provides a new way of reading the gospel, understanding the purpose of the life and the nature of one’s mission;

- this life on the margins gives birth to a new spirituality which moves one away from the triumphant Christ to serving the fragile Christ in a desolate world.

- and finally, from the Desert Fathers and Mothers we learn that to be a radical one needs to be a contemplative. Sheer immersion in activism won’t make us effective, but a new vision and passion will. These come from the places of prayer, solitude and contemplation.

Clearly the Desert Fathers and Mothers and their formative wisdom is relevant for present day Radical Evangelicals as they seek to leave their jobs in the West and enter the slums of major Asian cities to be an incarnational presence in serving the poorest of the poor.

2 – Benedictine Spirituality

St. Benedict of Nursia (480-546 A.D.) founder of the Grant Monastery at Monte Cassino began a way of life in community which was crystalised in his Rule which has powerfully shaped monastic communities up to the present.

This way of life represents a balance between prayer, reading and learning, practical daily work, the practice of hospitality and the formation of those seeking this vocation.

While Benedictine Monasteries are a different kind of community to that of Radical Evangelicals, because the latter are specifically oriented to living amongst the poor, much can be learned from the Benedictines.

One of the most basic lessons for Radical Evangelicals, who are so often focused on seeking to do the extraordinary in their mission and ministry, is the vision of the blessedness of the ordinary or the sanctity of the rhythms of daily life. The ordinary, such as preparing a meal, should not be seen as a distraction but as a priestly task. So the challenge from the Benedictines is to live the ordinary extraordinarily well. This means living a spirituality of daily life as a form of worship and service.

Living the ordinary well – and surely there is much of the ordinary living in the slums of Asia’s major cities – calls us then to live God-mindful lives. This means in both the excitement of a major missional project and in chatting to neighbours and in doing basic house duties, we are invited to be open to see and hear what God is saying and doing. Attentiveness is clearly a key theme.

While the vow to remain single may not be a primary vow for Radical Evangelicals other Benedictine vows with particular application are appropriate. These include the vow of conversatio Morum, the commitment to live a life of ongoing openness to God and the work of the Spirit resulting in a life of continuous conversion and transformation. They also include the vow of obedience in that Radical Evangelicals serving the poor both want to obey God and the gospel, but also submit themselves to community practices, priorities and ministries.

The traditional vow of stability practiced in Benedictine Monasteries is also appropriate for Radical Evangelicals. To live incarnationally in serving the poor and to bring shalom to a particular urban poor community is not the work of five minutes. It is the long haul of learning language and culture, befriending a community, working with them for change and transformation, doing the work of witness, building a faith community, addressing employment issues and working for permanent housing. This is like running a marathon. This is a long obedience. After two years of not too much happening one may want to move on. The vow of stability invites us to stay.

Two other important themes can be learned from the Benedictines. The first is the gift of rhythms. They seek to live a life of prayer, study and work. All three are integrated and important. All have to do with loving God and the neighbour.

Radical Evangelicals tend to live lives of imbalance. They are project-focused and activist. Their mantra is that there is so much to do, needs are so great, injustice is so rampant. And while this may be true, this cannot be the only dimension of one’s life and focus. Thus life needs to be brought into a greater balance so that life becomes not only more sustainable but also more joyful despite the challenges of poverty.

The challenge that the Benedictine vision brings to Radical Evangelicals is to more fully embrace the spiritual disciplines, including the spirituality of prayer and the spirituality of Sabbath. Prayer should be foundational both in its private and corporate forms and this is living in the friendship of God and in God’s purposes. Thus prayer is both nurturing and missional.

The spirituality of Sabbath is more than simply building into one’s life a time for rest. Rest so often stands in the service of work in that we rest to gain strength for our work. Sabbath, however, which is ‘time out’ which we can build into our day and week and so on, is very different to rest to gain energy for more work. It is holy leisure. It is God-oriented. It is renewal not for work per se but for life, for attentiveness for celebration.

All of this is meant to contribute to a more integrated way of living life. Thus while work is a given for so many Radical Evangelicals, prayer remains an ongoing challenge. And this needs to be complemented by the spirituality of study. This is loving God with all our mind.

This is particularly relevant for Radical Evangelicals as they seek to learn culture, to do community work and work for social transformation. This requires a lot of learning. But this too needs to be balanced with learning from scripture, theology and spirituality.

3 – Other Christian Traditions

So far we have briefly drawn on only two important Christian spirituality traditions and have attempted to show how these are relevant for a missional spirituality for Radical Evangelicals.

This is only a small beginning but hopefully is suggestive and productive enough to invite further reflection on other traditions of Christian spirituality. This I propose to do in a subsequent article where we will explore both Protestant as well as further Roman Catholic spiritual traditions.

Making Sense of our Own Lived Experience

A Radical Evangelical movement such as Servants to Asia’s Urban Poor has the opportunity to integrate three dimensions. It is to live and work in the biblical story seeking inspiration, direction and hope. It can draw from the distilled wisdom of the long march of the church in history which, when it was healthy, always combined a vision of God and neighbour, prayer and service and spirituality and the work for justice. And it can make sense of its own journey of life, prayer and service and develop some of its own distinctive spiritual practices in the light of Scripture and the tradition of the Church.

Let me briefly sketch out what that might look like:

- Servants, like other Radical Evangelical groups, has its own history of calling, community and mission. Some of this has appeared in book form. Much of it is in the memory of its members. Important themes could be gained from these writings and from interviewing Servants’ workers.

- Servants has its own distinctive five missional principles and its five values (Jack 7-8). A whole tradition of thinking and practice has developed around these principles and values. These could begin to form the basis for liturgical readings and reflections.

- Servants’ teams and workers in their journey of community and mission repeatedly go back to certain Scripture passages, sing certain hymns and find certain prayers helpful and relevant. This rich resource can be tapped in developing certain resources and practices that reflect this heritage.

- Over time in various Servants’ teams and in the forums which draw all workers together every three years, certain forms of celebration have developed. These forms could be generalized across the movement as a whole.

While all this may sound like an unhealthy process of routinization, it can be a way of retaining one’s heritage and creating a communal missional spirituality. This can include songs, scripture readings, readings from other spiritual resources, prayers – including prayers of lament, eucharistic practices, meal celebrations, fasting, foot washing, liturgical dance and many other spiritual practices that reflect both the life of the community and the nature of its service in the places of inequality and deprivation in Asia’s slums.

Conclusion

Radical Evangelicals, including Servants, are known for their incarnational ministry in service to the poor. As such, they are known for their self-sacrifice and their activism. And given the great needs of the poor in major cities, the challenge to do more is always there.

But Radical Evangelicals need to live a sustainable lifestyle of community and service. Therefore, to focus on a balanced way of living in the light of some of the Benedictine themes is important and complements the radicality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers that is also part of Radical Evangelicalism and the Servants’ ethos.

Moreover, Radical Evangelicals should be known for more than their activism. While we want to learn from them how to do community development, plant urban poor churches, train urban poor workers, do micro-economic development and work for social change, we also want to learn from them regarding Christian community, the practices of prayer, the other spiritual disciplines and a life of piety, simplicity and wholeness. In other words, we want to learn from them how to follow Jesus and to live lives to the glory of God, in communities of mutuality and care, in radical hospitality and in service of the poor. From living such lives new resources of spirituality will emerge to bless the body of Christ.

Places, programmes, people, priorities and prophecy may make an intriguing litany of alliteration – but they are also the realities which have either pushed us into theological reflection or the routes we have travelled after theological-‘-biblical truth has gripped us. Beneath and within all these emphases can’ be discerned theology: in the concluding section of this article I want to draw ‘out some of the theological insights and implications of urban mission.

Underlying Theology

Each phase of urban mission has either sprung from, or been compelled to re-discover, fundamental theological motifs. That theology has been hammered out in the crucible of experience and not the seclusion of a study. It has been marked by a return to biblical roots and by a developing lay movement. The geographical emphasis on place, the inner city, is matched by the theology of incarnation. In John’s Gospel the word is made flesh (John 1.14) and Paul speaks of the one who took the nature of a servant. He became like man and appeared in human likeness (Phil Z. 5-11).’ The Gospel begins with being – and being there. God’s pattern of identification and involvement is not answered by commuting congregations, fragmented participation or parachutist evangelists who come briefly – and go quickly. In ‘biblical history the purposes and grace of God are made real by committed people in specific places – Moses in Egypt, Jonah in Nineveh and Jesus at Calvary. Urban mission itself has pushed Christians into a renewal of the understanding of the theology of mission – in terms of width and depth. The equation of evangelism and mission has been challenged – mission is now seen in a total sense, embracing evangelism but holding together social action and political justice. Matthew 28 and Luke 4 join hands. The language of mission among inner city activists moves from church planting to unemployment, from political involvement to cross-cultural communication, from confrontation with other faiths, to concern about racism. In this sense mission becomes inclusive and total. But a deeper note has been struck. Death and resurrection are more than Bible words. They have become the· experience of congregations and individuals within the inner city. Paul’s prayer that he might ‘know the fellowship of his sufferings and the power of his resurrection’ becomes contemporary as inner city Christians enter the hurt and work towards the healing of the urban people and communities. The concern’ for’ the urban poor sprang from, and is sustained by, the consistent biblical emphasis on the value of each human being, made in the ‘image of God’. The doctrine of inclusion is a constant reminder that individuals are the object of God’s love. The marginalised are centralised; it is Christian belief that the·single-parent, the elderly, the homeless and the abandoned are those loved by Jesus in the New Testament and by his people today. People matter and they matter to God. The fundamental belief in the worth, dignity and destiny of each individual is proclaimed in the face of the depersonalisation, collectivism and racism of contemporary culture.

The debate about urban priorities has taken the church into areas of theology that are proving to be uncomfortable and divisive. The biblical stress on Kingdom, the modern, uncertainty about society and the controversy about religion and politics point to unresolved tensions and a theological agenda that is still surfacing. Beneath the theology of society and the role of the Church lie profound issues – the insidious corruption of institutions as well as individuals is represented by the stress on structural sin and the assertion that many among the urban poor are ‘sinned against, .as well as sinning’. Finally, the note of urban, prophecy picks up the principle of doing rather than saying, of representing visually what is not heard audibly. The endeavour to flesh out the Gospel in community living or personal life-style owes much to the holistic theme of shalom. Wholeness for the individual, the healing of relationships and the unity of the community are all key-notes in the over-all shalom belief which refuses to allow religion to become purely cerebral or personalised.

Working out theology

The connection of the church’s mission in the world and human rights is basic; it is part of our definition as people of God. A separation of church and rights is like the separation of faith and works, words and deeds, theology and sociology, theory and practice. There is no biblical basis for these separations. Jesus said “I am the light of the world” then turned around and healed the blind. He said, “I am the resurrection and the life,” then turned around and raised Lazarus; and he himself arose to empower us to live the same kind of life, where words and deeds, technology and sociology, faith and works, flow out of our lives.

For the Average Anglican church/ community this represents a paradigm shift, where the congregation would be prepared to meet the wider community ‘at their point of need’. Local ministry would be located in the context. This included becoming aware of the social, demographic, geographical, historical factors that constituted the parish. This was an attempt to return the church to a positive urban focus within the wider community.

The working out of the theology of urban mission has profound implications for the whole church. These include the rediscovery of Bible themes which have been ignored or disobeyed; the emergence of a model for theological reconstruction; the questioning of the accepted programmes of theological training; and a relevance that springs from the issue-centred realities that demand a response. The rediscovery of Bible themes like justice, jubilee, and shalom have been made by a generation of urban activists – in the Third World, the U .S.A. and the U.K. The stress of the Third World on freedom from oppression has led to liberation theology (and it should be studied in context rather than dismissed as alien to the U.K.) and the black-white divide in U.S.A. society has’ seen the emergence of justice as a key issue. In the United Kingdom books like Roger Dowley’s ‘Towards the Rediscovery of a Lost Bequest’ (a work-book written by a layman after a life-time in inner London) have become standard text-books.

The emergence of a model has been seen in the base community. The Consultation on World Evangelisation report in 1980 spoke of the unanimous conclusion of the ‘working party on urban poor: We believe the basic strategy of the evangelisation of the urban poor is the creation or renewal of communities in which Christians live and share equally with others. These communities function as a holistic, redemptive presence among the poor, operate under indigenous leadership, demonstrate God’s love, and invite men, women and children to repentance, faith and participation in God’s Kingdom.

The questioning of’ traditional programmes of theological training has come from ‘two directions. The casualty’ rate among the professional ministry led church leaders to an induction course that prepared incoming leaders by a process of participation and reflection; this involves an unlearning before authentic ministry can begin. The strong cultural bonds of the black-led churches’ initiated a series of leadership-training groups in the context which have been followed elsewhere by a wide range of urban programmes for gifted laypeople who do not wish to go to a theological college but prepare for leadership in their own context. The relevance of a theology that springs from issue-centred reality is illustrated by the study-book ‘New Humanity’ by Sue Conlan and Maurice Hobbs, which takes the biblical material on race and justice and sets it against the painful history of British racism. Both the writers have been heavily involved professionally and personally in race issues and have shared in the group Evangelical Christians for Racial Justice. They, like other groups centred on politics, unemployment or poverty, have been compelled to rediscover the Bible themes that alone can make an adequate foundation for response and action. The theology of urban mission is now much more than a hopeful phrase. The evidence of books and projects, the historical pilgrimage of the urban church set out in the distinct phases and the underlying theological roots all come together in a strongly interwoven tapestry of pattern and colour that has already changed inner city Christians and now reaches out to question and challenge the prevailing theologies of the established denominations.

The Gospel message

THEOLOGY OF INCLUSION expand – see my blogs

- Miroslav Volf embrace

- Willie Jennings whiteness

- Stolen Generations and refugees

- John Swinton – intellectual disability, mental illness and dementia

- Glen Stassen – A Thicker Jesus – Incarnational Discipleship in a Secular Age

- Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context,by David P. Gushee and Glen H. Stassen

When I was growing up the death of Jesus Christ on a cross was the defining centre of my understanding of Christianity. Moreover, as an explanation of something as unique as the mechanism by which God sets the world right, Christ-as-substitute-for-my-sin was, not without its problems. For example, the Christ-as-the-substitute model treats reconciliation as transactional rather than relational.

For many, it continues to be the central and defining message.

Yet, it is not, to my reading, the way the New Testament articulates the good news. Substitionary, penal atonement makes sin, guilt and retribution the central themes of faith. It gives us a theology that focuses on what’s wrong with us, which issues in language declaring we are unlovable (but, God who is love, loves us despite our unloveliness), culpable (you struggle to find any sense that our problem might be the power of sin, or the systems in which we live), incapable (but we can do things in Christ’s strength, whatever that means) and is so firmly fixed on the individual – Christ died to save sinners – that the collective is easily ignored. Which has now created a huge problem of individualism in countless congregations around the country.

But what if we made resurrection the centre of the gospel? What if at the centre of the universe lay not an act of retribution but God’s declaration that he will break the cycle of violence and retribution by absorbing whatever evil we throw at him, forgiving and creating new life and a renewed world? Would it not change the way we frame faith, the way we speak of ourselves, the way we relate to God and engage with the world?

The good news of the gospel cannot and should not be reduced to the declaration that Jesus died to pay the penalty for our sins. I question whether the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement (PSA), R. Murray Brown’s influence – which is a fairly detailed way of saying how it is Christ’s death saves us from the consequences of sin – is in fact an accurate representation of the teaching of the New Testament.

Given Paul is the writer most closely associated with PSA, it would be reasonable to assume that if PSA is the heart of the gospel it would stand out boldly in his summaries of the gospel. Likewise, one might expect it would feature heavily in his preaching. Paul discusses dimensions of the gospel right throughout his letters, but on three occasions he pauses to define the content of his gospel: in Romans 1, in 1 Corinthians 15, and in 2 Timothy 2. I also reviewed the two sermons of Paul’s that are recorded in the book of Acts. Not a single one of Paul’s gospel summaries nor his Acts sermons comes close to describing the gospel in terms of PSA. There’s no discussion of propitiation or expiation, no mention of Christ bearing the wrath of God upon the cross, no elaboration of how it is that his death serves to save.

Did Paul understand that PSA is the mechanism by which God saves us? Surely Paul’s own summaries of the gospel and his preaching of the gospel should reinforce the notion that PSA is the heart of gospel. For Paul the gospel seems to focus on the glorious news that God raised Jesus from the dead. That we are deeply and truly loved. That even the deepest pits of despair cannot extinguish the possibilities of hope. That life has purpose and meaning. That death, disease, violence, and all those things that plague our lives and our world are not the final word. That injustice will finally be overturned.

In the New Testament the emphasis is not on Jesus’ death but on Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. None of the evangelistic sermons in Acts are about on-the-cross-Jesus-paid-the-penalty-for-your-sins. Rather they consistently declare that Jesus lived a good life, was executed by his opponents but that God raised him from the dead, making him Lord of all. In taking this approach the early Christian evangelists focused not on what Jesus did for me (pay the penalty for my sin) but on who Jesus is for me (the One designated by God as the leader, prototype and creator of a new humanity).

The good news is not that Christ died for our sins, but that Christ died for our sins, was buried and raised on the third day. These must be held together, and any theology that treats the resurrection as an afterthought is not the theology of the earliest Christian writers.

Leadership and change

Leadership with great vision can provide a new direction in ministry. The next phase could be one of a cautious approach that allows for the taking of risk, heralding a new era in experimenting with ministry at the parish level. Bridges between local community and parish church can be intentionally built. The era of foray into experimental ministry through Christian community development strategies could be commenced decisively

Barriers to Urban Mission:

- The churches appear to be supportive of mission (amongst their own) and yet closed communities. It is very much ‘unto their own’. The congregations appear to relate intimately together in terms of cliquey groups.

- People who are regular Anglican attenders are not representative of the wider community profile. That is, the socio-economic status is largely middle to upper class even in older working class suburbs.

- The elderly are over-represented and the under 30’s under-represented.

- Congregations do not reflect the wider community in terms of ‘ethnic profile’.

- Congregations are not representative of gender balance. More women than men being regular attenders.

- The majority people attending are white Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs), with a sprinkling of Sri Lankans, Indians and Pacific Islanders who were also previously from Anglican backgrounds.

- Congregations are having difficulty coping with the rapidly, changing nature of their community, especially the multi-cultural aspect of the changing nature of their neighbourhoods.

- Teaching mainly conducted through clergy seems to be mainly exegetical with little application to the wider community especially regarding the present community/socio/political context of the church.

- People struggling in their faith and newcomers are often not adequately followed up as clerical resources are exhausted and the laity is not organized effectively.

- There is a lack of trained Lay leadership to cope with the demands of the community.

- Often such congregational resources are stretched to the limit and so numerically declining congregations do not have the capacity to fund and employ additional church staff.

- Previously, ministry has functioned along monolingual, mono-cultural, similar class lines. This assumes a maintenance mode, rather than a missional one.

- There is a relatively culturally homogeneous, monolingual view of community.

- There is little formal ongoing missionary outreach into the wider community tying gospel and social action/programmes together.

- Contrary to the dominant practise that the Anglican church need only reach white Anglo-Saxons, it is argued that the churches need to reach the ever-increasing culturally diverse populations.

Opportunities for Urban Mission:

- The needs of the wider community must be identified so that there is an entry point for outreach, using the Christian community development model.

- In order to encourage urban mission, it is important that it is encouraged from the pulpit/leadership.

- If church life needs to be more accessible to the outsider, then the form of church life may need to be re-considered and changed.

- It could be argued that mission activity should not occur until church life is adequately developed. Here it is argued that mission activity is vital to dynamic church life.

- It is essential that attention is constantly paid to pastoral aspects of church life in order to support congregational participation in missionary activity.

- The construction and meaning of ‘culture’ needs analysis, especially the creation of alternative communities.

- The same principles of communication through culture can be applied to young people culture, the elderly, and other groups using the incarnational paradigm.

The Church, the ‘poor’ and belonging