Governments needs to close respect gap with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

March 17, 2015

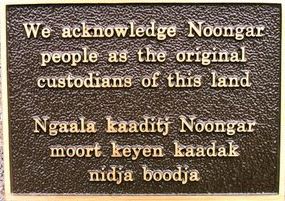

Historic Turning Point for Noongar People in progress towards Self-Determination

March 30, 2015This photograph has become an enduring image of business executives who place the interests and profits of their corporations above the public interest. It shows chief executives of leading tobacco companies in the US swearing before members of a House of Representatives’ Committee that they did not believe nicotine was addictive (1994).

Subsequent (1998) litigation against big tobacco resulted in the Master Settlement Agreement, one outcome was the release of 14 million internal tobacco company documents (80 million pages). These documents proved that the tobacco industry had known since the early 1950s that tobacco was giving people heart disease and lung cancer and that nicotine was physically addictive. The documents also demonstrated that Tobacco executives did everything they could to keep this information covered up, and to fabricate studies attempting to disprove that cigarettes were killing people.

see: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/;jsessionid=2997A512FC2E38048EB249846B19EF23.tobacco04

George Monbiot has written that extensively that both the oil and tobacco lobbies recognized early on that their “best chance of avoiding regulation was to challenge the scientific consensus. Citing a memo from the tobacco company Brown and Williamson noted, ‘Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy.’”

see: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/sep/19/ethicalliving.g2

The book Merchants of Doubt, by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, argues this in more detail.

The authors outline how a group of high-level scientists, with extensive political connections, ran effective campaigns to mislead the public and deny well-established scientific knowledge over four decades. While addressing tobacco, acid rain, the ozone hole, global warming, and DDT, Oreskes and Conway expose this dark corner of the American scientific community, showing how the ideology of free market fundamentalism, aided by a too-compliant media, has skewed public understanding of some of the most pressing issues of our era.

The authors suggest that two key questions that should be asked of anyone who casts doubt on science. Firstly, who are they? Do they have a vested interest in challenging the scientific knowledge for some reason that has nothing to do with science? And secondly: how well has the scientific community been studying this? It’s important to look at the process by which scientists come to their conclusions and whether, after studying for some period of time, they have come to some kind of consensus, or general agreement. And if someone is challenging that consensus, we need to be questioning their integrity.

In modern science, there’s a myth that scientific knowledge is based on an individual genius who has a eureka moment, and that’s when new knowledge is created. Most science doesn’t come from a eureka moment; it comes from hard work. The process is all the different scientists who scrutinize claims, the scientists who go to meetings, ask questions, and submit their work to peer review; and once the research is published, people read the paper and do follow-ups. This is a long process that goes on. It doesn’t happen overnight’ typically important scientific claims take decades to become established.

The book, Merchants of Doubt, shows that many of the people who attacked the science of smoking also attacked climate change. The book argues cogently that normal scientists don’t move to totally different, unrelated issues. They usually have one area of expertise. It is highly unlikely that anyone could be an oncologist and a climate scientist at same time. That was the key that this was nt a scientific debate.

Many people assume this is just a story about people being corrupted by industry. Why would prize-winning scientists risk their scientific reputations to work for both the tobacco and energy industries and distort science. The authors suggest that’s where the ideology came in. They started reading scientists letters, what they had written. Oreskes and Conway discovered this free-market ideology, holds the view that any government intervention is a slippery slope towards socialism.

Oreskes and Conway suggest that tobacco and climate change have a lot in common that motivates researchers to mess with the science. They are both places where you have a problem created by a product, and that product is legal. It’s not illegal to sell or use the product; the authors have discovered it has created this gigantic problem. It’s market failure: the market created a problem it then has not remedied. This is a legitimate place for government intervention — carbon tax, emissions trading systems, various options one can draw on — but all require the government to do something. Oreskes and Conway outline that in the US these industries tap into an anti-government strand in American culture and politics: the government that governs best governs least.

Now the acclaimed book Merchants of Doubt, has been turned into a film.