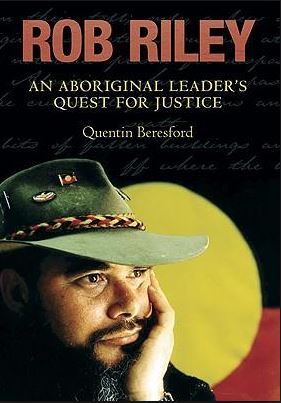

Rob Riley: An Aboriginal Leader’s Quest for Justice

March 9, 2016Swan Native and Half Caste Mission: the Anglican Church and Aboriginal Children in Western Australia from 1838 to 1920**

March 9, 2016

This book is a history of Noongar people; it is based on a history report that was tendered as expert evidence to the Federal Court in the litigation of the Single Noongar Claim and has been subject to rigorous cross-examination.

In contrast to the long established conventions about the history of Noongar people, in particular the thesis of ‘extinction’, this volume argues a thesis of ‘survival’.

Most histories of WA keep Noongar people on the margins of colonial history, where they are characterized as a group of people who were quickly dominated, dispersed, stripped of culture, and, made extinct. When reading conventional histories, it is not hard to get the idea that Noongar history is little more than a history of institutionalization, separation, attempts at assimilation and relentless state control.

This book shows how Noongar law, custom and culture have survived notwithstanding the impact of settlement, regardless of the values that the colony was built upon and despite the conventional historical records.

This volume demonstrates a history of survival of the Noongar people and overturns three central conventions of Western Australian history.

The first convention is that Noongar people were unable to adjust to the European presence; that they were devastated by introduced disease, killings, and loss of long-established hunting land.

The second is the convention that because of how Aboriginal people were racially classed, Noongar people were all but ‘extinct’, bred out, by the turn of the 20th century.

The third convention was that real Aboriginal people inhabited ‘remote’ Australia. The result of this convention was that Noongar people in the south-west, as in other parts of settled Australia, were seen to undergo cultural loss and breakdown.

These conventions have been challenged but their influence persists.

The book shows how, these conventions can be found in early writings of colonial administrators and through the writings of people like Daisy Bates and reinforced by more recent anthropologists such as the late Ronald and Catherine Berndt.

The role of the anthropology of Noongar people is disturbing. It was decided long ago that Noongar people had lost their culture. Professor Berndt stated that Noongar culture was ‘beyond recovery’, judgments made without any fieldwork or without talking to one Noongar person.

Published histories almost exclusively consist of these types of statements from writers who have fallen into the lap of complacency, making assertions with little analysis or critical thought.

Perhaps not surprisingly, these ideas are still very much alive and well today. They were seen in the hostile position the State took in the Single Noongar Claim arguing that Europeans settlers killed all the Aboriginal people of Perth intentionally through shooting or unintentionally through introduced disease. It was also argued that the ‘Noongar people’ from Perth weren’t Noongar at all. This is in stark contrast to the countless public events where State Government Ministers and representatives continue to acknowledge Noongar people as the traditional owners of Perth!

There are literally thousands of records describing Noongar people in negative terms and histories which detail what was done to Noongar people. Yet these same Noongar People have adapted to the new arrivals and sustained traditions and culture. This volume presents a new storyline of Noongar history to renew the historical record and show how Noongar people and families survived, evaded government surveillance and indeed thrived.

This is a story that shows Noongar people were here when the Europeans came and are still here today as a people, as a culture, proud and strong.

Post Script:

May 19, 2010

Noongar Native Title history book wins major award.

In the presentation speech the Minister said:

“The judges felt this book had the potential to alter the path of

historical Aboriginal research and that the work has led to a paradigm

shift in the way Aboriginal culture and identity is defined and understood.”

Previously posted 2010