3 Reasons Why Martin Luther King Jr. May Be America’s Most Outstanding Theologian

April 4, 2016

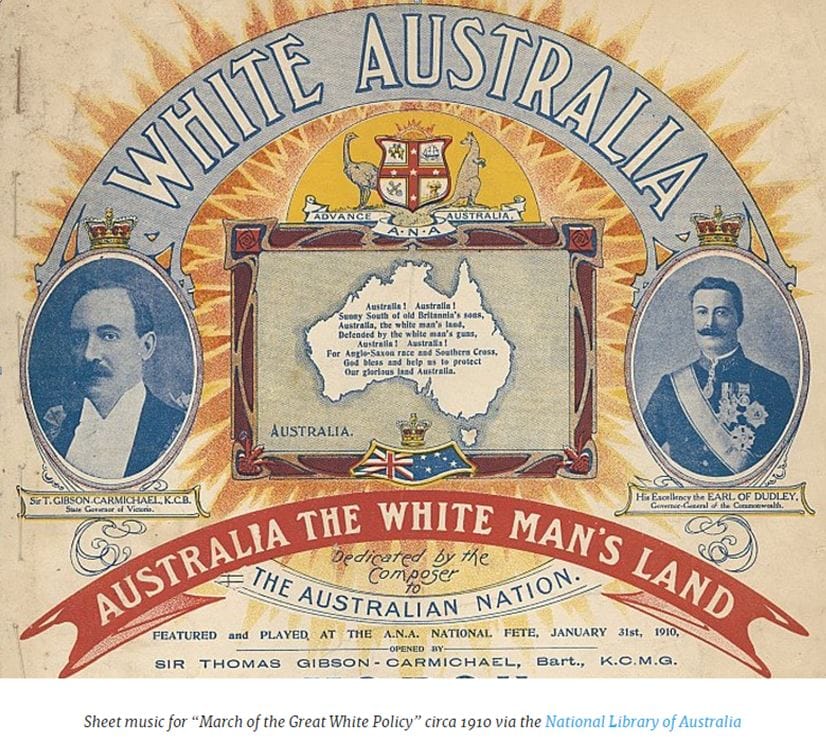

Establishing Racism: the Australian way

April 4, 2016I have spent many years talking, thinking and writing about racism, social justice and inclusion. but I had not realized just how deeply rooted racism is in Australia until I actually started reading more deeply about the white Australia policy along with non-white thinkers and theologians.

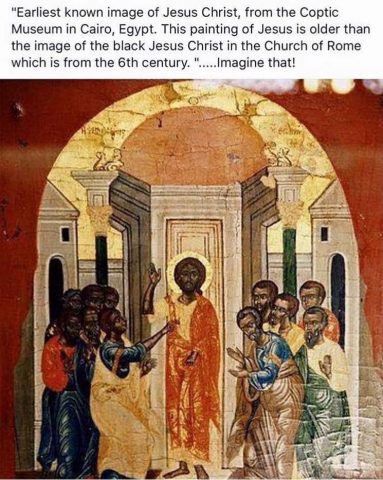

Growing up I had an image of Jesus with blue eyes, and flowing golden hair, this Jesus was good-looking, magnificent—and indisputably white. Hardly Semitic! It was this representation of Christ that shaped my early faith and my understanding of the world around me. This is the elusive racism that is untaught in the early faith development so many white Christians and the one that operates in the background of our faith communities.

Mostly we’re completely unaware of this shaping of how we think, but when the Jesus you perceive looks like you it’s difficult not to view yourself with a distorted lens; one where you are more in the image of God than another and possibly more deserving of respect. This in turn leads to a misperception of how we view ‘the other’. While I would not have accepted any obvious prejudice or intolerance, looking back I’ve been able to see how my unreal portrait of Jesus informed an unreal story about God and about people who were not white. It made me more fearful and less compassionate.

Around 30 years ago I began to realize the invisible barrier it has often been to me more clearly seeing and being moved by the inequality around me. Sure, I’d say that God so loved the world and could recite that Jesus died for all people, but subconsciously believing that I was what God looked like insulated me from the suffering outside my window when it proved too frightening or inconvenient.

And the saddest thing is how many people like me, who should know better. In these days of such division and intolerance, the silence of so much of the white Christian Church here has been conspicuous. They’re never at a loss for words, when discussing matters of sexuality or sexual orientation; but are silent on race. The refusal of so many white Christians to recognize the disparity of experience across colour lines tells a story that they still worship a very White Jesus and probably still see God as in their own image.

This representation of the white Australian Church a quiet, complicit spectator, it should be challenging its own. The more I come to understand the character of Jesus, the more I’m convinced that I have to reject and discard this image of a White Christ, not because I’m ashamed of my whiteness but because I don’t want to make an idol of it.

Australia is fast becoming a place of unfriendliness and disconnect, largely because white people of faith have failed to accurately recognize and fight for the God in their non-white brothers and sisters; it’s a sin that warrants of our full repentance. I’ve never accepted the narrative of our country as a “Christian nation”, but from its very inception power and privilege have been in the hands of religious people with a white Christ. They have written the story of faith and race in this country—and it isn’t pretty. It needs to be re-directed. We cannot be silent in these days or we will be proving our allegiance is not to God but to our own likeness and self-preservation.

I have been trying to work out exactly what it is I can say to the situation. I live a comfortable and privileged life, that is the context and framework from which I speak, or in which I speak. I recently read an article by Willie Jennings titled Overcoming Racial Faith; it addresses white privilege as an approach to our understanding theology and I realized what exactly it is that needs to be said, especially to conservative white Christians. Jennings’ analysis in his book The Christian Imagination provides ground-breaking accounts of this long- standing social harm. Moving way beyond the individualist and structural accounts, Jennings links racism to colonialism and Christianity. His analysis of the deep connections between the Christian imagination and racism fleshes out colour-blindness in a very thorough way. Jennings’ work is not only a significant account of the social-institutional and global forms racism has taken for centuries, but also draws attention to the entanglement of Christianity and racism for hundreds of years. In short, the topic of race cannot be treated as a secondary “ethics” issue, (or a thing of the past), but is entailed in Christianity and its dominant forms of theology. Jennings shows how ostensibly well-intentioned Christian faith is and has always been shaped by bias and connects racism to the long history of European colonialism, which is more entangled with Christianity than many of us ever realized.

What is deceptive about white privilege is that it is different from blatant racism or bias. A privileged person’s heart may be free from racist thoughts or biased attitudes, but may still fail to see how the very privilege afforded to him or her shapes how he or she interprets and understands the situations and circumstances of people without privilege.

This is a common theme when conservative and middle of the road Christians talk about racism: It’s a problem of the heart. Part of this comes from Christians fascination with the “disposition of the heart” and growing focus on individual salvation, or spirituality, both symptoms of a stunted theology that fails to take into account the social implications of Christianity. But I think it also stems from the fact that conservative and middle of the road Christians do not engage with thinkers and theologians who are not white.

When I have read theologies of race, what has become clear is that racism is a much deeper infection than most theologians acknowledge. White privilege may not be conscious, sure, but racism is so much deeper than conscious hatred of those different from yourself. Racism applies to structures, to society, to aesthetics, to participation and so much more. It is these racist structures and systems within Australian society that have bred white privilege, hence white privilege is inherently an outcome of “blatant” racism. To not acknowledge as much is to actually give in to and perpetuate a racist system which continues to belittle the struggles of non-white people by seeing Australia as a “post-racial” or “post- colonial ” nation.

The reality is that racism is extremely subtle. White normativity is promulgated in the ways that we as a society continue to define the ideal. Something that has been quite topical recently is film and television. Whites are far and away the largest represented race on film. Miranda Tapsell has rightly drawn this to our attention and many rigorous academic studies have been done on race in popular movies. The results are both shaming and disturbing.

This perpetuates the myth that white is normative and good, while non-white bodies are less important, less moral, and less intelligent than their white counterparts. This is what I mean when I talk about a “structural problem of racism.” We are probably not conscious of the attitudes that we carry that are racist, the attitudes that continue to belittle the black body in favor of white normality.

But then let’s consider our history and the designing of a white utopia.

Establish Racism: the Australian way

Racism is not simply a problem of the heart, it’s not an act or an attitude, it’s an issue that has deeply infected Australian society since the very foundations of this nation and one that will take much more drastic measures than simply acknowledging that it exists and demanding reconciliation.

So yes, let’s continue acknowledging the fact that white privilege is a very real problem. But don’t stop there. White privilege is only a symptom of the greater structural racism infecting our society. Until we begin to take the hard steps of actually attempting to engage with other races, we can’t move forward. Until we start taking non-white thinkers just as seriously as we take white thinkers, our theology and practice will be stunted. Until whites take the step of acknowledging our role in perpetuating white normality and a racist society instead of demanding that non-whites become more like us, true reconciliation will not be attained. The problem is not just the heart, it’s society in general. The answer is not in overcoming our own racist attitudes, it’s stepping into the political sphere and actually starting to work toward the common good.

Palm Sunday is an amazing part of the Christian narrative and perhaps we skip over what it means and its importance because we know the next chapter. Like reading the last page of a whodunit, before savouring on all the clues in the lead up to the conclusion.

On Palm Sunday we learn to look each other in the eye and celebrate the differences that are the essence of our humanity. This adds quality and depth to the faith journey we share. Each of us acknowledges that what we hold in common is more precious than either our fractured histories or past prejudices.

Reading Matthew’s account (Matthew 21:1-10), we explore the pathos and tragedy of one man’s journey. This story remains the centrepiece of our Christian affirmation. It is Jesus’ unique story from Palm Procession to Upper Room to Calvary.

Each of us in our own way reflects on what Jesus’s dying and re-birth means for our own dying and re-birth. It may awaken in us the power of redemption, a refreshed discipleship, a renewed commitment to be God’s people for our own time.

However, the text demands a different reading. It is not a mere recollection of a past event. It is not the celebration of one more martyr for a cause. We may engage the theology of this text in different ways. We may understand Jesus’ life and ministry within the different frameworks of our upbringing or personal awakening.

But the awesome quality of this text is to place the living God at the centre of our discovery as we celebrate the differences that are the essence of our humanity.

Palm Sunday is the story of people distracted by power, arrogance, prejudice, ethnic rivalry and isolation. The image repeats these tensions in each subsequent event that marks the road to the cross. There is a moment of gathering, where people sit together in an Upper Room, sense each other’s presence and embrace the other. But almost at once they too are distracted by power, arrogance, prejudice, ethnic rivalry and isolation. The pattern of life around us tells its own squalid story of the same power, arrogance, prejudice, ethnic rivalry and isolation.

Then and now the question shapes about leadership based on love, acceptance and generosity of spirit. Then and now, the destiny of the Christian community is to challenge the false values that turn our eyes away from each other. There, in the very seeing and inner awareness of the other we are in the presence of God and we celebrate the differences that are the essence of our humanity. Why else did Jesus so intensely link love of God a, love of neighbour?

I despair as I face the silence of our churches over white privilege, refugees, ethnic hatreds, prejudice and the isolation of those abandoned by our systems. I learn to live with the determination that the greatest gift we all have is to steadily look each other in the eye and celebrate the differences that are the essence of our humanity.

So yes, let’s continue acknowledging the fact that white privilege is a very real problem. But don’t stop there. White privilege is only a symptom of the greater structural racism infecting our society. Until we begin to take the hard steps of actually attempting to engage with other races, we can’t move forward. Until we start taking non-white thinkers just as seriously as we take white thinkers, our theology and practice will be stunted. Until whites take the step of acknowledging our role in perpetuating white normality and a racist society instead of demanding that non-whites become more like us, true reconciliation will not be attained. The problem is not just the heart, it is society in general. The answer is not in overcoming our own attitudes; it’s stepping into the political sphere and actually starting to work toward the common good.